Book of Genesis

“When God began to create heaven and earth,

and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep

. . . God said, ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light.”

The stories in the Book of Genesis are a rich narrative inheritance woven throughout our culture, our literature, our language, almost into our unconscious. From the origin stories of Creation, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and the Great Flood, on through the patriarchal narratives of Abraham and Isaac, Jacob and Esau, and Joseph and his brothers, Genesis records a grand account of creation, destruction, regeneration; faith and disobedience; promise and fulfillment. It tells how a people understands their beginnings, their place in the world and their relationship to the divine.

In this study, we will explore how these stories attempt to understand our humanity, the nature of divinity, morality, the sacred and the profane. This study will read the impressive translation of Genesis by Robert Alter, which honors the meanings and literary strategies of the ancient Hebrew and conveys them in fluent English prose.

SALON DETAILS

- Six meeting study, also available as a one-meeting intensive study of Chapters 1 – 11 of Genesis.

- Text: The translation of Genesis we will use for this study will be by Robert Alter. It can be found in either of the two editions below, which are available new and used in the UK:

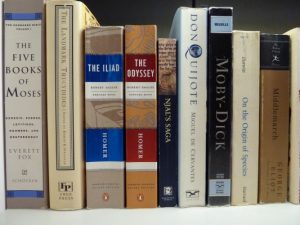

- Genesis: Translation and Commentary by Robert Alter; W. W. Norton & Company; New Ed edition (14 Jan. 1998); ISBN-13: 978-0393316704

OR - The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary by Robert Alter; W. W. Norton & Company (28 Oct. 2008); ISBN-13: 978-0393333930

- Genesis: Translation and Commentary by Robert Alter; W. W. Norton & Company; New Ed edition (14 Jan. 1998); ISBN-13: 978-0393316704